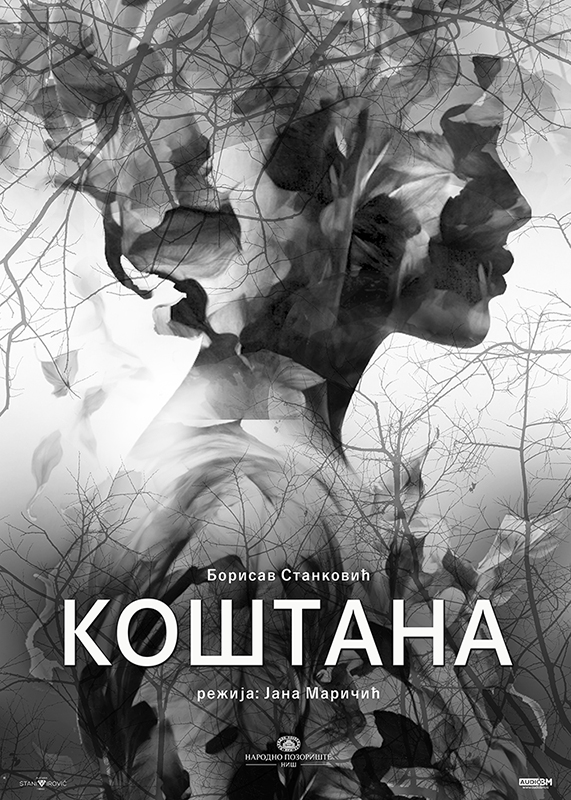

KOŠTANA

They don’t know that each of my novels makes me live through the illness.

Borisav Stanković (Vranje, March 31, 1876 – Belgrade, October 22, 1927)

In the “History of New Serbian Literature”, written and published by Jovan Skerlić in the best years of his creativity, Borisav Stanković was awarded first place among new Serbian storytellers. For Skerlić, he was “the greatest talent that ever existed in Serbian literature”, a writer who produced “one of the best and most complete novels in Serbian literature”, an artist “with things that are perfect”.

Pavle Popović in his “Review of Serbian Literature” notes: “Borisav Stanković created a masterpiece of painting and poetry.”

These two most authoritative persons of the age placed him with such flattering opinions on a pedestal, from which no one could remove him; although there were those who, out of conviction or some other motives, tried to at least reduce his importance, but without any significant success, no one tried to challenge him completely and everyone recognized his exceptional giftedness and originality.

Branimir Ćosić drew attention to this first, as if arguing with those who viewed him from the “more controversial sides”:

“It is possible that there have been writers with broader conceptions, that there will be, but none of them has gone deeper than Stanković into the vortex of basic passions and needs.” A Stanković man or woman is always a man or a woman of flesh and blood, who live a difficult and bloody life of a man and a woman tied with all their weight to a limited, senseless, crazy cramped physiological existence, which is in vain plowed by subconscious complexes that seek complete living, crossing all boundaries of space and time (imprisonment of a person in his own body, inability to experience passion, regret for youth).”

Isidora Sekulić in the essay “Bore Stanković’s dark vilayet” talks about a rare and original writer, but wonders if Stanković was aware of what he gave in his most inspired moments, creating his best works. Especially when he spoke about the decay of the old and the birth of the new Vranje, about the atmosphere of the old Vranje and, especially, when he spoke about children and youth; as if he created rather by instinct, by hunch. And when he analyzes the main characters and what is poetic about them, talking about Sofka’s father, Effendi-Mita, who, in order to stay afloat as much as possible, sells his own daughter to a peasant, without any major scruples; and then, as if in a hurry, he adds: “there is another Mita, the famous Mitke, which is perhaps Bora’s greatest poetry!”

Sima Pandurović, Bora’s “comrade” from the bar, sometime before his death said in a conversation with journalists about Bora:

“He was a rather silent man, speaking briefly, brokenly, as if to himself, without developed phrases and sentences. I did not hear him talk about his written or imagined works either, but I know that he took his calling seriously and valued his literary work. On one occasion, an editorial office asked him for a short story, but urgently and as soon as possible. Bora got angry, grumbled and told me: “They think it’s just like that: give the story when they need it.” They don’t know that each of my novels makes me live through the illness.’ I believe that he was telling the truth. He carried his life and nostalgia for his homeland deep within himself, creating his work under the imperative of one feeling. He experienced his passions and the crises of his heroes. Hence, I think, his stories radiate warmth and give a full impression of real life.”

Velibor Gligorić stood up wholeheartedly for Stanković and his work, not only as a critic but also as a person. He wrote an extremely warm report about his visit to Stanković’s house in Vršačka Street in Belgrade, where he says, among other things:

“In the basis of human nature, he saw the desire for the light and beauty of life. For him, that is the greatest value of living, the greatest value of life. That is why he experienced with great exaltation the spring of life, the spring in human nature, and that is why the person closest to him was a man with a singing imagination and a warm heart. In the works of Bora Stanković, there is a very intense poetic longing for personal freedom and human happiness.”

Milan Bogdanović spoke about Borisav Stanković’s work:

“In the psychology of this entire world, which Borisav Stanković brings to life in his novels, short stories and dramas, sensory passion prevails. That Vranje life and world is one corner of the Slavic Balkans, where the Slavic painful soul and anxious sensitivity crossed paths with a lot of blood. There are really many other people’s traces in them. He left the most profound oriental sensualism, which, so to speak, flooded the content of Stanković’s works. Passion, carnal passion is a big motive here… No one is protected from the claws of passion. And if the personality is socially and psychologically more complex, the passion is more destructive in it.”

Prepared by Tamara Milosavljević

BIOGRAPHY OF THE DIRECTOR

Jana Maričić was born in Belgrade on October 4, 1984. She graduated in theater and radio directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, in the class of professors Slavenko Saletović and Iva Milošević. She has directed at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Belgrade Drama Theatre, Bitef Theatre, Boško Buha Theatre, National Theater in Sombor, National Theater in Subotica, Serbian National Theater in Novi Sad, National Theater in Kikinda, Knjaževsko-Serbian Theater in Kragujevac.

A WORD FROM THE DIRECTOR

In the carefully prepared text by the editor of this program, there is a quote from Bora Stanković, who says: “They think it’s just like that: give the story when they need it.”

They don’t know that each of my novels makes me live through the illness.”

When on the terrace of the NT foyer, the general manager of the National Theater in Niš unexpectedly invited me to direct Koštana, it seemed as if he thought it was just like that provide a play for the Day of the Theater, we need it for then. However, he knew that it’s not just like that, and I knew what was coming.

Afraid, but brave; passionate, soulful, painful, fiery; suspicious, but also curious, raw, fierce, confused, tender, these actors followed the rhythm of my instinct against their reasoning. That’s why they, unlike these Bora’s, know: each of my shows makes me live through the illness. I thank them for playing that secret.

Koštana by Borisav Stanković on stage of the Niš National Theatre

Borisav Stanković entered the literary space of Serbia as a storyteller in 1899, with the collection From the Old Gospel. A year later, as Milan Grol testifies, Stanković, at the urging of the dramaturge of the National Theater (then named the Royal Serbian National Theater) Dragomir Janković, elaborates a motif from the story Our Christmas about Fatima, “the famous, busty gypsy woman with a white face, black and round eyes (Afterwards, the municipality had to marry her by force, because when they meet her, they forget lunch, dinner and night. Until dawn they drink brandy, cover her hair and body with money, beat their wives and drive them out of the house because of her”), and writes the play Koštana.

Stanković’s Koštana premiered for the first time at the National Theater in Belgrade, on June 22, 1900. Stanković himself wrote about the first perceptions of the show: “In addition, the first staging of the drama Koštana fails because of an already entrenched formed oppinion among the audience: that everything that comes from southern regions (Niš, Vranje, Leskovac) should be funny and a caricature (Sremac)”. However, after the more than positive reviews of Koštana by Jovan Skerlić, in 1901, continues Stanković, “it becomes the most popular piece on the stage.” The history of Serbian theater clearly shows that Stanković’s Koštana has retained its popularity even after more than a hundred years since its premiere.

Nevertheless, despite its enormous popularity, Stanković, due to “significant technical flaws” and genre heterogeneity, reworked Koštana several times, “expanding it in dialogue and scenes” and changing its genre definition: 1900 – theater play in four acts; 1902 – a play from the life of Vranje, in four acts, with singing; 1905 – dramatic story; 1924 – a play from the life of Vranje with songs.

Stanković creates a drama from the tradition of folk pieces with singing, which were the most popular drama genre on the theater stages in Serbia at the end of the 19th century. However, he betrays the canons of this genre in several ways – from abandoning the village as a place of action, betraying the mandatory happy ending where the righteous representatives of patriarchal morality win”, to the introduction of drama elements of naturalism, symbolism and neo-romanticism: he devotes himself to a deeper psychological analysis of the characters, surrounded by unsympathetic and repressive urbanized environment, created by the transition from one environment to another, from natural to monetary economy, from patriarchal to civil culture.

The historical time of the drama Koštana, as a problem of the time distance between the time of the play and the time of the audience, i.e. as the fact that this drama is realized primarily through a clear iconic and indexical reading in and about the “time of the premiere”, was directly performed by Borisav Stanković. What is meant here is that the historical time of the creation of the play and the first performance coincides with the historical moment that is discussed in the plot: under the List of Faces is written “Vranje. The present.”

In an attempt at a general typological characterization of the historical period which Stanković is directly addressing, the existence of a strong desire to establish a system (state, dynasty, social order) and the need for individualization, as a sign of freedom, and their mutual negation, marked not only the period of the premiere of Koštana but also the entire 20th and the beginning of the 21st century in the Serbian people.

Whether it is read through this recognized fact, which indicates that the drama, through events directly related to the time of the drama’s creation, abolishes any historical-temporal distance between the audience and the scene itself, or through the explicitly stated theatrical-aesthetic ideology of that period – socially engaged drama, with a lot of “real perception and local color”, which writes “concrete literature” about and from modern times – the interpretation of pragmatics is essentially dependent on the tensions that can be decoded from the socio-cultural circumstances of the time of the first performance. Underscoring that his knowledge coincides with the knowledge of a well-informed audience about all aspects of public and private life, codes of legislation and customs, Stanković forms the dramatic tension in Koštana on a whole series of oppositional socio-cultural paradigms that determine the characters and their relationships, both within the drama itself and in extra-artistic reality: past – present, rich – poor, upper social class – lower social class, socially powerful – not socially powerful, successful – unsuccessful, family member – not family member, male – female, young – old, child – parent , healthy – sick, Serbina – not Serbian, etc.

Staying on the trail of previous interpretations of Koštana, especially the dramatic text, we will agree with Petar Marjanović’s statement: “Researchers of Stanković’s literary work have noted several of his basic themes: the transience of life and love, ‘regret for youth’ (or more precisely: Regret for what was not, which didn’t even happen, which was missed); the desire to go ‘somewhere’, because the life one is living is not the right one. Isidora Sekulić also pointed to the topic of the tragedy of children, “who become victims of their father, father-in-law, brother, the almighty God of men”. – All these topics were also raised in Koštana. And yet – if I were to try to single out the basic one – I would opt for the aspiration for a free life, which Koštana manifests to the greatest extent. It also gives birth to the basic dramatic conflict between the representatives of two opposite views on life (the young singer and dancer – Gypsy Koštana – and Arsa, the president of the municipality, representative of social order and defender of all canons inviolable in the life of the society of that time.)”

In Koštana, therefore, two plots can be recognized, one at the level of the development of the motive of freedom, liberation from legislative and customary constraints, which we will mark as the main plot, and the second, which is subordinate to it, the development of the plot in love between Koštana and Stojan (subplot). A complex network of thematically equivalent plots is created around the axes of the main and secondary plots in the relationships between Hadži Toma and Kata, Arsa and Mitket, Koštana and Mitket, Koštana and her parents.

The composition of the plot of the drama belongs to the so-called type. natural constructions of a literary and artistic work. At the same time, it is brought under the analytical dramaturgy procedure in which the past has a decisive influence on the events of the present. The conflict, namely, does not develop from an unambiguous initial situation in which the antagonistic forces are clearly defined, but its basis and essence are located in the time before the beginning of the stage presentation. In this way, the plot is created by learning about an event from the past that directs the action of the character, as well as the entire play, to the other side.

The temporal organization of Koštana’s plot is simple and prospective: it starts from the chosen moment (Stojan joins the unbelted people of Vranje in enjoying Koštana’s song and dance), which was moved immediately before the stage presentation itself and, in accordance with natural time, lasts until the moment when Koštana is taken away in the wedding carriage. Between each image (act) there is a temporal discontinuity.

However, the first three acts take place in close chronological order and almost coincide with the classicist assumptions of “two tours of the sun”. By this compression of time, from the point of view of the perception of theatrical time, the first three acts become a reproduction of an ever-present past, spread in a straight line towards the future, in which nothing new happens, and where the movement is a repetition of the same custom, those events that were indicated at the beginning of the dramatic narrative. However, this classicist closure, as an ideological image of a symmetrical, perfectly ordered world, is destroyed by Stanković with events that stand independently in relation to the main plot, or begin suddenly, from the accumulated dissatisfaction of the soul, and which, as such, with their own temporal dimension, in time stage presentations are held together by space. This primarily refers to the fact that the opposition centralist-rationalist code, which unites every other example of binary coding, is conditioned by chronological blocks of time: before and now. Each of these categories runs parallel and cross-cutting. The first of them flows in the evocative spaces of Hadži Toma, Arsa and Mitko, while the current time of living in Vranje is placed in the dialogue parts of all the characters. In this way, the time of Koštana becomes complicated and expands from the present to the past.

The chronology of the sequence of events is formed around the border year of 1878, when Niš, Vranje and Leskovac were liberated from the Turks and annexed to Serbia. Koštana is so tightly bound to this non-artistic referent that it can be said that it derives from it, that it also produces the theme and descends: “Vranje in the time before the very end of the Turkish rule and immediately after the liberation is the dominant chronotype of his (Stanković’s – cf. S. Ž. M.) prose (and dramas – prim S. Ž. M.), which largely conditions the fateful breaks that his heroes face”. The fact that Hadži Toma refers to the laws and customs from the “Turkish era” in front of Arsa, and that Arsa applies those same laws by force by marrying Koštana to Asan, implicitly suggests Stanković’s pessimism about the possibility of changing customs and habits even in the time of the premiere.

The fourth act, due to its temporal distance, appears as a kind of epilogue. “And the epilogue, according to tradition, is a part of the piece ‘beyond fiction’ (conclusions are drawn from the story, the audience is thanked); he combined the fable with reality, and thus differed from the denouement as the last fictional segment.” In Stanković, the fourth act has the function of a fictional afterword, characteristic of a novelistic (novelistic) narrative, not a dramatic narrative. Koštana has two classic, irreversible final events in the fourth act. Many of our literary critics and theater experts think that Stanković could have ended Koštana with the third act. With Arsa’s decision to marry Koštana to Asan, a man she does not love, the order returns to the initial stable situation. His decision ended an event. The fourth act is therefore completely outside the dramatic action and is actually the beginning of a new story.

Koštana abounds in simultaneous events. Almost during the entire duration of the stage action, music, song and sounds of the street come from the offstage space. However, due to their simultaneity with the events of the stage presentation, they do not decisively affect the development of the plot. As a rule, they are part of the sound curtain, ambient background, artistic ornamentation and realistic confirmation of what the characters are saying in front of the audience.

In the scriptural sense, off-stage action is defined within didascalies. They are, in fact, stage markings of place and time, instructions for actors, they determine the spatial-temporal coordinates of a fictitious dramatic event. As with other playwrights of that time, not only in Serbia, but also in wider areas, Stanković’s didaskalies are scattered and, with emphasised attention, they ambiently structure the space of events and shape the portraits of the characters. Critics emphasized their “novelistic precision”, resulting from Stanković’s realistic and almost photographic gift. However, they go beyond the boundaries of realistic numinosity and rise to a higher, symbolic level. As Ljiljana Pešikan Ljuštanović observes, “the woven, cluttered, dark and muted exteriors of the rich pilgrim’s home and in Koštana function on the level of realistic motivation of the characters who belong to them, indicating social and economic power, but, at the same time, they become a space of imprisonment and lack of freedom.” That’s why Stojan only seemingly offers salvation to Koštana. (…) Koštana knows that there is no idyllic spring garden in reality: ‘Should I not move, not leave the room, but just sit there, be silent, look at the moonlight…’ The rationality of her fear of the pilgrim’s house confirms the fate of all members of Hadži Toma’s family, and not only the existential security of the women – Stana and Kate – which could be conditioned by the patriarchal family hierarchy, but also the position of the men, the guardians of order, Stojan and Hadži Toma. The richness of the house, embodied in carpets, sumptuous carvings, silence and subdued light, stifles the vitality and instinctive impulses of its occupants.”

Summarizing the results for the purpose of a limited analysis, we point out the relocation of the performance of the National Theater in Niš, adapted and directed by Jana Maričić, premiering on March 11 in 2024

– The spatial-temporal deviation of the performance (scenography, costume design, compositional solutions), approaches the historical time of the performance, while retaining the compositional structure of the pretext.

– Jana Maričić and the ensemble of the Niš National Theater make a fundamental shift in the conception of the relationship between the characters of Mitke and Salča. Their relationship, or rather their unfulfilled love from the past, is the realistic motive for initiating the action and the prism through which all other thematic axes of the conflict are refracted. In this way, the character of Koštana overcomes her inhibitions, derived from the framework of realist literature “study from life” and mirage eroticism. There is no doubt that Jana Maričić, at the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century, felt the need to point out the fact that at all levels of the social order people live are alike. All the more the tragedy of Koštana of the Niš National Theater becomes a tragedy of society.

Associate Professor Spasoje Ž. Milovanović

Koštana by Borisav Stanković on stage of the Niš National Theatre

1901, 1905, 1910, 1918, 1919, 1922, 1925.

December 1, 1931, Dragoslav Kandić

1937

October 7,1941, Josif Srdanović

March 31, 1945, Josif Srdanović

December 20, 1945, Svetozar Milutinović

February 1, 1947, Dragutin Todić

February 1, 1949, Dušan Antonijević

October 05, 1965, Rajko Radojković

September 28, 1971, Gradimir Mirković

November 12, 1984. b. Aleksandar Djordjević

April 17, 1993, Branislav Mićunović

March 11, 2024, Jana Maričić

Koštana is the Diploma performance for Una Kostić.

Cast

Koštana, singer and dancer - Una Kostić

Salče, her mother - Maja Vukojević Cvetković

Hadži Toma - Aleksandar Marinković

Stojan, his son -Danilo Milenković

Kata, wife of Hadži Toma - Evgenija Stanković

Magda, restaurant manager - Ivana Nedović

Arsa, president of the municipality - Miloš Cvetković

Mitka, brother of Arsa - Dejan Lilić,

Vaska, daughter of Arsa - Natalija Jović

Stana, daughter of Hadži-Toma - Nađa Nedović Tekinder

Koca, her friend - Nikolija Mičić

Cop - Petar Miljuš

Musicians:

Aleksandar Stevanović (accordion)

Nenad Tančić (Tarabuka)

Vojkan Dobrosavljević (clarinet)

Goran Savić (guitar)

Predrag Branković (bass)

Technical Crew

Stage manager: Dobrila Marjanović

Sound design: Slobodan Ilić

Lighting design: Dejan Cvetković

Light operator: David Jovanović

Prompter: Vanja Šukleta

Assistant stage manager: Natalija Cindrić

српски

српски English

English